Dr. Pieter A. Schippers is an affable man, a learned and inventive man, and a few centuries back he and his family would have been in the stocks for practicing unnatural agriculture.

The Schipperses grow crops that never touch Mother Earth.

They use hydroponics, in the form of an ingenious, home-built soilless growing system developed by Dr. Schippers during his years as an academic horticulturist. Plants love it, especially the butterhead lettuce that the family's Hydro Harvest partnership trucks from its Ashby, Massachusetts, greenhouses, week in, week out, at the rate of some 210,000 heads per year. The Stop & Shop supermarket chain buys it all and retails it---even with a high markup---at prices competitive with Sunbelt imports.

The Schipperses are breaking new ground (albeit they might choose to put that some other way). It's not just the hydroponics, for an increasing number of commercial soilless growing operations have started up recently in the Northeast. Most of those are, however, high-cost installations marketing gourmet vegetables at ritzy prices (hydroponic produce does tend to look like seed catalogue ads); and they have been viewed mainly as faddish experiments in a specialty market, competing only with themselves. Now the Schipperses' Hydro Harvest is altering that picture. Out of sight on a back road in lovely Ashby, working their technological equivalent of a family farm, the Schippers clan is proving that hydroponic produce raised on a small scale can sell in the region's mass markets.

A Simple But Effective Hyrdoponic Farm

A Simple But Effective Hyrdoponic Farm

|

The homestead of the Hydro Harvest operation is a rambling, two-family house, fronting calmly on a pasture-sized lawn and infiltrated by seemingly countless dogs. Pieter Schippers and wife, Erien, occupy one half; son Skip and daughter-in-law Sandra, both holders of bachelor's degrees in horticulture, live in the other. It's homey and peaceful, but out the back drive domesticity gives way to the landscape of production: coal piled for greenhouse furnaces, lumber, rolls of plastic, big multipurpose barrels. Just past the small barn appears the centerpiece of the family business: three big (145 by 34 feet), quonset-shaped, plastic-covered greenhouses and one smaller one.

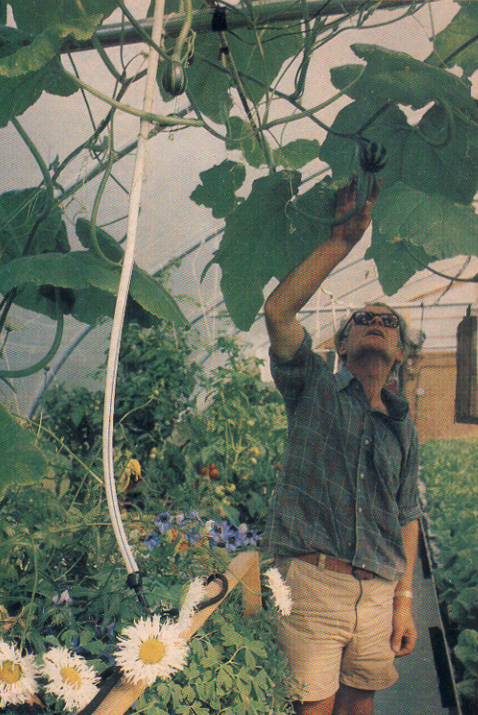

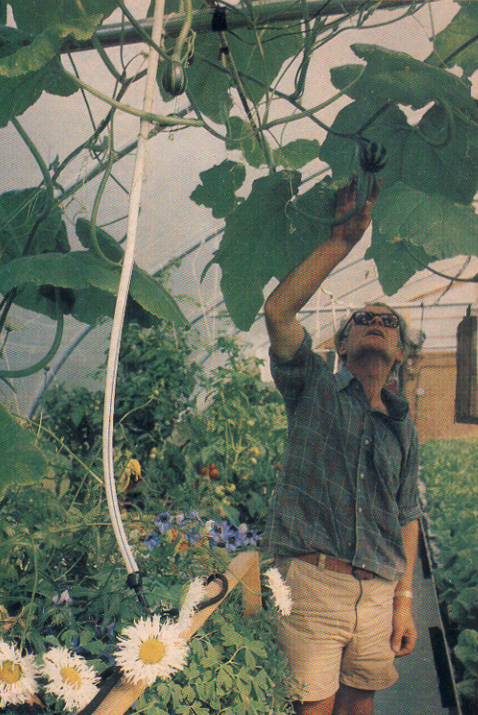

For counterpoint, the view also includes the fenced outlines of a large, failed vegetable garden, now choked with weeds. "Aha, you noticed," Dr. Schippers says, his Dutch origins still showing through in his accent. "We thought that would be a perfect place, but the soil was too wet." As a result, the family's kitchen garden was moved inside and out of the ground. Schippers opens the door to Greenhouse Number 1, and there---on waist-high tables running halfway along one luminous side wall---is a profuse, gorgeous mixed garden: cauliflower, dill, hush beans, cucumbers, asparagus, basil, chard, deiphiniurns, carrots, peppers, snapdragons, tomatoes, baby's breath---twenty-eight vegetables and flowers, all told, covering the spectrum from African violets to New Zealand spinach. They root in shallow beds of crushed perlite (a white, nutritionless mineral product) through which a nutrient-rich solution percolates. Carrots grow sideways when they reach the bottom of the bed. Tomatoes and other top-heavy plants are supported by strings from the greenhouse's framework above. Cucumber vines are trained up and along the same framework, dangling their fruits in midair. "The main problem," says a smiling Sandra Schippers, who is most responsible for the garden, "is that I put in too many varieties, and they all just took off." The result is more than meals for the family; it's also dramatic confirmation of Dr. Schippers's assertion that hydroponics will do a good job on almost anything you'd want to grow.

Greenhouse Number 1 also holds a crop of watercress, but much of the interior space has been cleared for demonstration plantings needed for a training school in hydroponics which the Schipperses opened this past winter. That educational venture further diversified what is becoming a small family conglomerate. The Schipperses also run a consulting service for growers and would-be growers, and operate a modest operation supplying components for home-built hydroponic systems, offering materials that may be difficult to get in custom sizes or small quantities (odd lengths of sheet plastic, small pumps, some nutrient chemicals).

But the family's basic preoccupation and livelihood are still to be found in Greenhouses 2 and 3: lettuce, some 11,000 heads per house (in varying stages of maturation) at any given time. (The fourth and smallest greenhouse is home to seedlings.) Weekly yields from each lettuce house range from 2,700 salable heads in summer to perhaps 1,000 in deep winter, for an annual total of some 105,000---copious green testimony to the effectiveness of the Schippers hydroponic design. The income from sales gives an equally strong endorsement to the economics of the system, particularly as constructed and operated with family labor. The Schipperses built and equipped their large greenhouses for about $15,000 apiece, or $3 per square foot ---roughly what an unequipped similar structure would have cost if installed by a dealer. And the resulting low overhead pays off; Hydro Harvest wholesales lettuce for just 37½ cents per head, and almost half of that is profit. Gross annual sales from each greenhouse approach $40,000, higher than the expectations of almost three quarters of American farms. Projected net proceeds per year from each greenhouse, counting payment to themselves for labor as well as profit, run as high as $24,000-higher than the national median for all family incomes and more than twice as high as the net revenue of the average American farm. (The Schipperses discuss cost and price figures, but do not divulge family income.) Annual profit alone potentially returns as much as 120 per cent of the basic greenhouse investment. But Dr. Schippers cautions that new growers adopting his system can't expect the same yields---vegetative or financial---that Hydro Harvest gets. "It takes time," he says, "and lots of experience to get your best efficiencies." Even operating at a lesser level of competence, however, Hydro Harvest clearly still would he in the running for the best-in-show award among homegrown enterprises.

For Pieter Schippers, fifty-seven, this happy home agribusiness marks the end of a long trail through darkest academia. A plant physiologist for thirty years, Schippers's specialty for much of his career---spent mainly at Cornell University's Horticultural Research Laboratory at Riverhead, Long Island---was the storage problems of harvested root crops.

"For twenty years," Schippers says, "I was a potato man," and his expressive face adds a grimace, evoking visions of numberless dim cellars of stored spuds. "But after a while, well, where can you go with that?"

In Schippers's case, it was up to the greenhouse, where in the mid-1970's his work intersected with a British breakthrough in hydroponics called the Nutrient Film Technique. This stripped-down method seeds plants into peat or plastic foam plugs, places the seedlings (with external bracing as necessary) in sloping troughs or beds, and keeps their bare roots moist with a continuously circulating flow of nutrient-rich fluids.

Pieter Schippers set out to make the Nutrient Film Technique more flexible. He devised systems of almost every size and shape, using cheap materials such as plastic wastebaskets and miniature pumps. He invented an easy test to determine when solutions need a boost of nutrients. He adopted the use of fluid-retaining perlite so the pumps that circulate the nutrients can be shut off for longer periods, saving energy costs and ensuring that mechanical failure won't result in dead plants, as can happen in systems that keep roots bare.

And most important, he developed movable spacing for his crops, enabling him to fit more plants into each greenhouse. "See," Schippers says, "it doesn't really matter what you grow in---soil, hydroponic solution, whatever. So long as you give a plant what it likes the yield will be the same. Hydroponics makes it easier to do that in many ways, but more important, the limited space and weight factors let you use a movable system, and I found out that the movable system can give you a thirty-five-per cent increase in output per planting."

The practical translation of that finding---a Hydro Harvest production greenhouse---stuns the visitor with its nearly wall-to-wall contents of green. It's a rabbit's dreamland: three 9-foot-wide mats of densely planted lettuce, elevated waist-high and slightly aslant, running the length of the greenhouse with only narrow aisles between. Everything looks ready to eat, but closer inspection reveals that each house-long strip of plants starts with seedlings at the far end and offers mature heads only nearest the greenhouse entrance. The seemingly unbroken ribbons of planting actually consist of hundreds of nine-foot sections of white plastic rain gutter laid side by side like ties on a railroad, each filled with perlite and sporting eleven lettuce plants spaced along its length.

In fact, each of the house-long swaths of plants is actually a kind of conveyor belt. The planting gutters are organized in four sections of 84 each---with 924 heads per section. A system of wheeled skids and support rails beneath the gutters allows each section to be moved and allows sections to be spaced farther apart to accommodate the increasing size of their plants.

A Simple But Effective Hyrdoponic Farm

A Simple But Effective Hyrdoponic Farm

|

A section of seedlings, placed on the rails with gutters edge to edge, begins the process at the back end of the greenhouse. After one to two weeks of growth, depending on the season, the whole section is rolled forward. As the gutters are moved ahead, they are also spread apart on the skids, to make room for more growth. Then a new section of seedlings is added behind the section that has advanced. More moves follow after additional growth, until there are four sections on the tracks, and the initial planting has reached the other end of the house---by which time its gutters have been spaced several inches apart to correspond with the breadth of full-grown plants. After harvest, the liberated gutters in the lead section are topped off with new perlite and shifted to the rear to take on more seedlings, while the three remaining sections move ahead again.

Seedling development is much more mundane. The lettuce is seeded into small peat plugs, which sit pressed together in wide pans of nutrient fluid, soaking it up like sponges, until the new plants are big enough to go into the perlite. Roots, seeking the source of nutrients, simply grow through the essentially nutritionless plugs.

The system makes optimum use of available space and ensures that plants are ready for harvesting when they arrive at the end of the greenhouse from which they will be shipped. The system also works well for feeding. The support rails under the gutters are designed so that the gutters slope for drainage. Long, black, four-inch vinyl pipes, suspended over the high edge of the gutters, act as reservoirs for the nutrient fluid. Hundreds of tubes project from the larger pipes, and the nutrient solution drips into the perlite and heads downslope. What the plants don't drink and the perlite doesn't absorb runs out the lower ends of the gutters into drain channels, which carry this unused solution to sumps, where pumps return it to the overhead pipes.

So, even with all the movement and respacing involved, the feeding system remains stationary while the plants cycle by. And the produce rolls out regularly.

"I always had it in mind to retire early," Schippers says. "When I found out what the movable system would do, I knew I'd be crazy not to try it." That was particularly true because, according to Schippers, Cornell was not interested in his findings. He says that those in charge of vegetables there "decided in 1973 that the fuel price increases meant the end of greenhouse vegetable growing in the region, so they stopped putting any emphasis on it."

Schippers's son Skip and daughter-in-law Sandra, however, were already operating a small Schippers-model greenhouse at their home in Ithaca, New York, and they believed that Dr. Schippers saw the future more clearly than did Cornell's policy makers. So, in 1980, the Ashby property was found, bought, and then---despite timidity at banks' loan windows--mortgaged sufficiently to provide capital for Hydro Harvest.

"It all came together," Pieter Schippers says, and the frown of the potato man is replaced by a wide smile of satisfaction.

Aisles in the Hydro Harvest greenhouses are narrow. Human movement is complicated by the shoulder-high overhanging nutrient-feed pipes, and by the protruding ends of the planting gutters that jut into hips and waists. So even though the Schipperses are all lean and agile and accustomed to the restricted space, unplanned collisions occur. This morning it is Dr. Schippers, backing up as he cleans a drain trough, who knocks the end gutter off a neighboring section. It falls awkwardly, disgorging lettuce and perlite onto the black plastic tarpaulin floor. "Oops," he says.

"The same one again," Sandra says, laughing and obviously recalling recent mishaps. "That one just seems to keep getting it."

To a visitor it looks as though half a box of lettuce has just gone down the tubes; after all, critics have long charged that hydroponic plants need pampering, being too delicate to survive shocks that conventionally grown varieties shrug off. But Sandra simply lifts the gutter back into position, and casually, rapidly, she and Schippers smooth the disturbed perlite and stuff the dislodged lettuce roots back into it. A later check of the same gutter shows that everything is fine. Pampered plants? "That's complete nonsense," Pieter Schippers says.

Hydroponics is also subject to some other criticism---particularly from the organic-growing community---about its supposed need for heavy preventive spraying of pesticides, its alleged susceptibility to the rapid spread of plant diseases, and its seeming dependence on nutrients derived from petrochemicals.

Local evidence is contrary. Of six hydroponic growers interviewed recently, none uses preventive spraying. "We just wouldn't do that," Skip Schippers says; and recently Hydro Harvest dealt with an infestation of springtails without resorting to pesticides. None of these six growers has ever lost a crop to disease, either. In fact, Pieter Schippers believes that traditional soil-culture greenhouses are probably more susceptible to hostile microbes than are hydroponic systems. In his research days, he recalls, "I started out growing lettuce in a peat-vermiculite mixture, and right away I had disease, disease, disease. So I thought, why not get rid of the organic material? That's what carries the organisms. And it worked."

As for petrochemical-based nutrient solutions, soilless growers are no less-and no more-vulnerable to criticism than conventional farmers who use chemical fertilizers. Most hydroponic nutrient solutions are simply refined, stronger versions of those fertilizers. One hydroponic equipment dealer now offers an organically based nutrient solution, however, and Cape Cod's New Alchemy Institute, a leading research

facility in the fields of alternative agriculture and appropriate technology, recently came out on the side of organic hydroponics. An article by New Alchemist Carl Baum in the organization's Spring 1980 Newsletter reported higher-than-average yields and excellent flavor in a variety of crops grown in effluents from fish tanks and nutrients from other organic sources.

But other criticisms of soilless growing hit the mark. The Nutrient Film Technique's seeming simplicity, for instance, often leads to false promotion of hydroponic rigs as technical marvels that one simply plugs in and ignores until it's time to eat. In fact, hydroponic growing demands unusual care and attention. "It needs more attention to detail than normal growing," according to Skip Schippers. Special details, that is, such as checking the potency of the nutrient fluid and correcting inbalances; matching the nutrient-flow rate with plant-transpiration loss; scheduling seeding to keep up with production; monitoring chemical composition and acidity of water supply (the latter can affect nutrient formulas); mixing chemicals, maintaining pumps, operating back-up generators, and cleaning sumps and drip tubes. The esoteric tasks of hydroponics are neither mentally nor physically overwhelming, but they do require special knowledge, and they are required in addition to the daily plant care and periodic harvesting that any greenhouse demands. Errors or breakdowns in hydroponic growing can be disastrous, particularly in systems with bare-rooted plants. A mistake in mixing nutrients or a broken pump can quickly convert a crop to compost.

To set up a hydroponic system requires considerable capital. And the growing method is a "step away from the land," as one critic puts it. Many supporters of the family farm are quick to point out that the technological approach of hydroponics is exactly the sort of enterprise calculated to attract the investment forces that increasingly dominate American agriculture through control of capital and centralization of ownership. The flip side of New Alchemy's findings, for instance, is that giant corporations such as General Mills, Control Data, and General Electric arc experimenting with fully enclosed, artificially lit, mechanized hydroponic factories, some even with carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere. At this level of technology, the method is called "controlled-environment growing.")

So, in the end, hydroponics appears to have potential for David and Goliath alike. But for the moment, it's the small-scale end of things that is flourishing. During the past three years, a health-oriented elite looking for high-quality vegetables has cleared the way here for companies marketing prefabricated greenhouses set up for the Nutrient Film Technique. These generally sell for about three times the cost per square foot of the Schipperses' installation. Their high-grade produce can, however, command handsome prices, and several growers using them claim returns on investment in the range of 33 per cent per ear. Add to that the tax advantages-hydroponic greenhouses qualify for accelerated depreciation like other agricultural installations---and it's not difficult to understand why more and more people-even those without any agricultural experience--- are lining up to give hydroponics a try. For example, at least a dozen single-family, commercial, prefabricated installations are scattered around eastern New York, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island, and are already sending tomatoes, cucumbers, and lettuce to market.

Simple Rain Gutters Worked Well

Simple Rain Gutters Worked Well

|

Dr. Schippers foresees economic doom for many of the prefabricated ventures. "I think that if you have to depend on higher prices just because it's hydroponic, you're in trouble." But trends in the national food system may he turning this apparent bit of sagacity inside out. Down in the Sunbelt a growing population and shrinking water supply mean that exports of produce from that direction will begin to slacken. As that happens, food prices in the North will rise faster than inflation, and alternative growing methods will become economically more attractive. Green house growing---which did indeed take a dive when petroleum prices ran up---could rebound, particularly with new solar technology and alternative sources of fuel to cut energy costs. With hydroponics arguably the most productive greenhouse-growing method, even high cost installations may find their prices becoming competitive.

Looking toward that prospect, some visionaries (or pick your own term) are discussing development of high-tech food factories in abandoned New England mills, where cheap hydroelectric power might be available. Corporate managers would run the show. But Pieter Schippers's bets are on the continuing spread of small businesses in hydroponics-a blending of family farms and greenhouses, helping to sustain and diversify regional agriculture rather than dominate it. Schippers believes that the economies of soulless growing show up most clearly in operations that aren't too complex and that require little staff besides family members.

With Hydro Harvest as his case in point, Schippers has a strong argument. The remarkable performance of the Ashby operation results directly from the abundance of ingenuity and effort the family has applied to implementing and adapting Schippers's system.

"You can't be lazy in this business," Skip says. Of course, the Schipperses' workload has included much design, construction, experimentation, and attention to other parts of the business as well as dealing with the lettuce. The Schipperses' estimate a need for one full-time worker per greenhouse of lettuce (with added assistance during harvest), but that calculation includes stretches of time for other chores as well. The labor requirements vary with the crop. One grower of soilless encumbers, for instance, takes care of two greenhouses himself with the aid of a student who comes in after school. A nearby tomato grower estimates that it takes only three hours of work per day to keep her single greenhouse going between twice-weekly harvests. But those harvests can last up to sixteen hours, counting both picking and packing the fruit, and they require additional help).

Lurking behind all estimates of labor requirements, however, is the basic commandment of soilless growing: thou shalt stick around. As in any situation involving mechanical life-support systems, unpredictable things can go wrong, and without quick action the consequences can be grave. "You've always got to be there when you've got something growing, Pieter Schippers says. In fact, says Sandra, "The way it is now, you can't ever get away.'

So the question arises: how big will Hydro Harvest itself become? With lettuce production booming, amid the training school recently begun, the family is almost at the point of making the transition from direct involvement in the greenhouses to the more rarefied state of business management. That shift is not an entirely welcome one.

"Already it's a panicky feeling when the harvest help [neighbors

working part-time] doesn't show," Sandra says. "Just the headache you

can get from personnel problems is a good reason not to get big. On the

other hand, I don't want to be picking the lettuce the rest of my life.

There's so many other exciting things to try in hydroponics." In

fact, the Schipperses have recently taken to selling cut flowers.

In the end, the dynamics of business growth may rule. After the

fourth greenhouse for seedlings has been well launched, Dr. Schippers

says, "I think we'll stop for a while." But the subject is not closed, and the family's talk focuses on the continuing need for more growing room, even with the new structure.

"Maybe we'll just have to build another greenhouse," Skip says.

"They'll just keep on building," Erien Schippers says with a laugh,

"until they have enough room or they run out of money."

"Yeah," Skip says, "but the trouble is that every time we build

another greenhouse, we make more money."

"Well," Pieter Schippers says, pressed on the point, "I think we'll

put up a couple more next year." He sees ten greenhouses as being the

outside limit. "It all depends on how interested we are in experimenting. We might do a whole house in watercress. Or we might do a whole house in strawberries." Spinach, Swiss chard, and tomatoes also make the lists of potential market crops the Schipperses might try.

Swelling business prospects, however, have not yet wiped out the

spirit and sentiment of horticultural research that got the enterprise

started. Back in Greenhouse Number 1, Pieter Schippers stands with

hands on hips, fondly envisioning new plantings to be added: egg-

plants, cucumber vines, peppers, tomatoes. Watercress in vertical arrays. Freesias. Strawberries.

"It's going to he wonderful," Schippers says, smiling. "A forest. A

mass of green. Fantastic!"

|

Home Hydroponics

DOES IT MAKE SENSE for home growers to try hydroponics?

If the goal is serious year-round growing in a smallish space, the answer is a cautious yes. Cautious, because a number of economic and personal considerations are involved in the decision. Yes, because both kits and plans are available for effective home-scale soilless growing.

Hydroponic systems can be light and compact, so they're good to use inside houses. No soil means less weight (although some kits use heavy gravel); and because the roots of hydroponically nourished plants don't need to spread and compete, the method allows for closer planting than conventional gardens permit.

How much sun the planting gets, of course, will determine the speed of growth and the abundance of the yield. Growers with solar spaces or sunny rooms are ahead in the game. In such situations, installation of a home-built family hydroponic garden---using cheap plastic wastebaskets, rain gutters, plywood covered with plastic sheeting--- might run as little as $125, and cost perhaps $4 per month to operate.

For those who want ready-made hydroponics, several companies are ready to oblige with kits.

The economics of the prefabricated units are troublesome, however, for instance, in a greenhouse one can grow far more than the average family can consume, and the system will only pay for itself if the owner can sell the surplus, That turns a hobby into a necessity. Even the smaller garden kits are questionable for families who just want fresh food to eat. The $749, 3-foot by 12-foot kit, for instance, claims a yield of 5 to 60 pounds of mixed produce per month. Averaging 47 pounds per month at a generous 75 cents per pound savings at the store, and subtracting an estimated $6 per month for operating costs, the kit takes more than two years to pay for itself.

All hydroponic systems have operating expenses greater than ordinary gardens; you've got to pay for nutrient solutions (one company offers an organic mixture), electricity for pumps, plastics of various sorts.

Hydroponic systems also require more care and attention than traditional gardens. Sellers of commercial-scale kits and plans all offer training schools to buyers, and home growers are well advised to get the same kind of preparatory information before starting-and then he ready to stick around. Hydroponic growers uniformly advise would-be users to plan to be available in case their systems need them. "Too many things can go wrong," says one dealer. "You can lose it all in an hour if you're not careful."

So the demands on your time and the considerable expense may argue against hydroponics at home. For the person who's handy and around a lot, however, it can work well. Eating those fresh vegetables while the snow flies outside can result in both savings on the food bill and satisfaction at mealtime.

|

|

PLEASE NOTE!

This article appeared in Country Journal magazine in August 1982. Unfortunately, Country Journal is now out of print, and Dr. Pieter Schippers has passed away. Nevertheless, the article may be of interest to some readers ---so we have included it for your perusal.)

|

For more information about these and the many uses of perlite in

hydroponic growing,

contact your local extension service, The Perlite

Institute (www.perlite.org) or:

The Schundler Company

10 Central Street

Nahant, MA 01908

(ph)732-287-2244

www.schundler.com

mailto:info@schundler.com